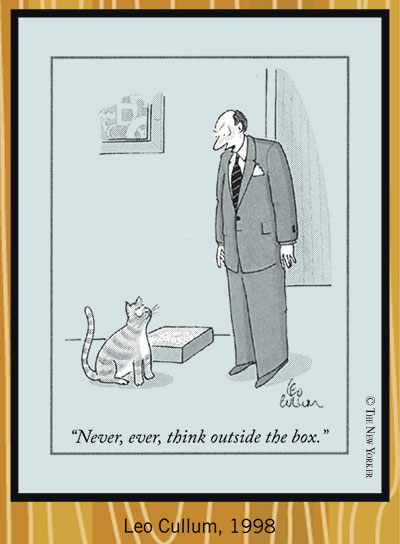

"If you can dream it, you can do it. Always remember, this whole thing started with a dream and a mouse."

|

| (Courtesy of epiclol.com) |

Or so Walt Disney said. And in many cases I have to agree with him, especially the mouse part...because in my case the mouse part's connected to the house part, and the house part's connected to, well, the stuff of nightmares.

This led to a couple of notable discoveries, the development of previously unknown skills, and, after almost two decades, a nicely remodeled house.

First the discoveries:

By some accounts the main portion of our house is approaching 140-150 years of age. Another way to look at it is that it's seen the turn of two centuries. Understandably, precious few things retain their original integrity after that many seasons, and, with the exception of the petrified oak beams in the basement which aren't going anywhere in the foreseeable century, the house is among them. My point is, at the time of purchase, the house was something significantly less than mouse-proof. We discovered this when cold weather set in and presumably chilly mousies began migrating in with alarming frequency. Which is to say any more often than never.

The house had been repeatedly remuddled over the years, a fact glaringly in evidence as we undertook our own updating, revitalising, and mouse-proofing projects. We learned pretty quickly that a seemingly simple project inevitably led to the discovery of four more that needed tending to before the original endeavor could be completed, and often not in the usual manner. "Level," "plumb," and "square" must have been relative terms back in the late 1800's, (as in distantly related and frequently disowned step-cousins.)

This is one reason I came home for lunch on a summer afternoon when the girls were young to find a hole in bathroom wall.

A wall-sized hole.

Looking into the backyard.

It had started as a simple, smallish, pre-hung window replacement.

Similarly, there was the late October evening during a partial roof reshingle gone awry in the time-management sense when it started to snow. In the dining room.

In retrospect, given the regularity with which we breached the exterior of the house, it's little wonder the wee critters helped themselves indoors on occasion.

| (This book by Jennifer Grant, Elizabeth and Cathy Crown suggests my house-sharing cats aren't alone.) |

Which is what led to the perfection of a previously unsuspected skill set. Perhaps because I am acutely aware of the potential for disease and the designated animal professional in the family, (not to mention vermin-averse), I became the best mouser in the house. I do not especially relish the title but somebody's gotta do it. In my case, 'it' initially involved a towel placed over the furry interloper who was then transported across the street to a more rodent-suitable field. (Color me guilty of residential profiling if you must but I make no apology for the fact that they were all summarily relegated to the corn field entirely without due process.) By the time my youngest daughter woke me one morning with a shriek and the words, "Mom, I need your mouse-catching skills," and I walked out the door with the mouse less than 30 seconds later I had graduated to merely lifting them by the tail...saved on laundry!

Thankfully, it's been awhile and with a bit of luck my mouse-nabbing endeavors have ended.

Anyone interested in a nicely remodeled and mouse-proofed 3-bedroom ranch in the country??